The Unsung Hero of Soil Regeneration

Modern agriculture has rediscovered an ancient wisdom - the transformative power of planting between growing seasons. This practice, far from being merely protective, actively rebuilds depleted soils from the ground up. When fields remain bare, they lose precious topsoil to wind and rain, but strategic plantings create living armor that shields and nourishes the earth beneath.

Beyond physical protection, these interim plantings perform remarkable feats underground. Their roots act as nature's plow, breaking up compacted earth while secreting compounds that feed microscopic soil life. This underground activity creates a thriving ecosystem where nutrients become more available to subsequent crops, reducing dependence on artificial inputs.

Nature's Carbon Capture Technology

Plants have perfected atmospheric carbon harvesting over millennia. What industrial solutions struggle to achieve, humble cover crops accomplish quietly through photosynthesis. Their leaves pull carbon from the air while their roots transfer it underground, where soil organisms transform it into stable organic matter. This natural process could sequester billions of tons of CO₂ if adopted widely.

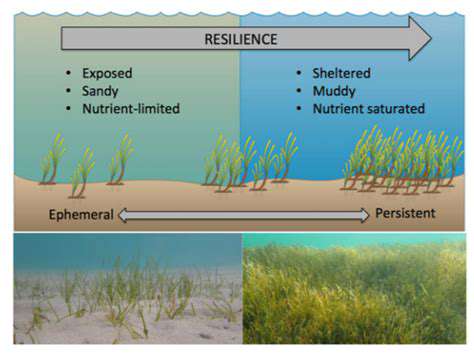

The carbon benefits multiply over time. As organic matter accumulates, soils become spongier, holding more water during droughts and resisting erosion during downpours. This improved resilience becomes particularly valuable as weather patterns grow more erratic, providing farmers with greater yield stability despite climatic challenges.

The Organic Weed Solution

Chemical herbicides revolutionized farming but at significant environmental cost. Cover crops offer a living alternative that suppresses unwanted plants through natural competition rather than toxic compounds. Fast-growing species form dense canopies that smother weeds while their root exudates can inhibit weed seed germination through biochemical means.

This natural weed control creates cascading benefits. Reduced herbicide use means fewer chemicals leaching into waterways and less damage to beneficial soil life. Farmers save on input costs while gaining cleaner fields for their cash crops - a win-win scenario that's attracting more producers each season.

Engineering Better Soil Architecture

Different cover crop species act as underground architects. Taproots like radishes drill deep, creating channels for water and air. Fibrous-rooted plants like rye weave dense networks that bind soil particles. This biological tillage creates ideal growing conditions without the soil disturbance that leads to erosion and organic matter loss.

The water management benefits prove particularly valuable. Fields with good structure absorb rainfall like a sponge, reducing runoff that carries away topsoil and fertilizers. During dry spells, the extra organic matter helps retain moisture longer, often making the difference between crop success and failure.

Nature's Fertilizer Factory

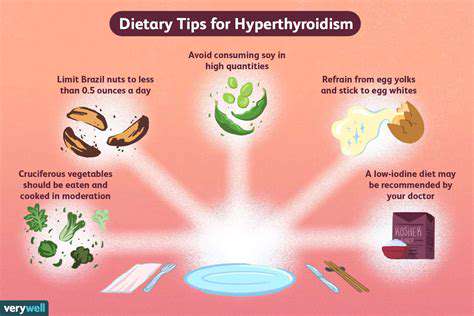

Certain cover crops perform alchemy with atmospheric nitrogen. Legumes partner with soil bacteria to fix nitrogen from the air, converting it into plant-available forms. When these plants decompose, they release this captured nitrogen along with other nutrients they've scavenged from deep soil layers.

This natural nutrient cycling reduces fertilizer bills while preventing the pollution caused by synthetic nitrogen. Excess commercial fertilizers often wash into waterways, causing algal blooms, but cover crops keep nutrients cycling within the farming system where they belong.

Creating Agricultural Ecosystems

Monoculture fields represent biological deserts compared to nature's diversity. Introducing cover crops begins rebuilding complex ecosystems above and below ground. Flowering species attract pollinators and beneficial insects that control pests. Underground, diverse root systems support a wider range of soil organisms.

This biodiversity creates natural checks and balances that reduce pest outbreaks and disease. Farmers who embrace this approach often find they need fewer pesticides as their fields become more ecologically balanced - another example of working with nature rather than against it.

The Long Game Pays Off

Transitioning to cover crops requires patience but delivers compounding returns. Initial investments in seed and planting give way to reduced input costs, improved yields, and greater drought resistance. Fields managed this way often outperform conventional ones during extreme weather events, proving their value when it matters most.

The economic case strengthens as consumers increasingly value sustainably grown products. Farmers practicing regenerative techniques often command premium prices while building land value through improved soil health - a legacy that benefits future generations.

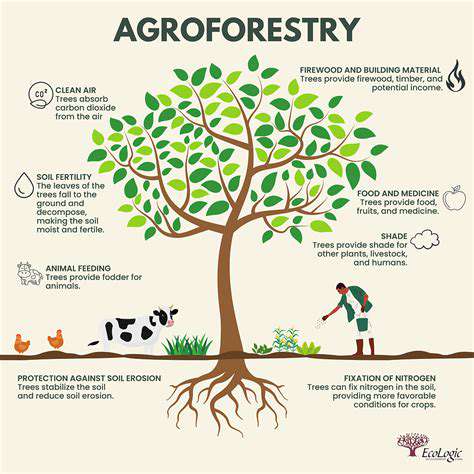

Agroforestry Systems: Integrating Trees and Crops for Maximum Carbon Storage

Blending Ancient Wisdom with Modern Science

Throughout history, humans cultivated food within woodland ecosystems. Today's agroforestry revives this integrated approach with contemporary ecological understanding. The combination of woody perennials with annual crops creates synergies that neither system achieves alone. Tree roots reach depths that annuals cannot, recycling nutrients and tapping into deep water reserves.

This layered approach mimics natural ecosystems, where different species occupy distinct niches. The result? Greater total productivity from the same land area, along with improved resilience to climate extremes. As weather patterns become less predictable, such diversified systems offer farmers valuable risk management.

Tailored Solutions for Every Landscape

Agroforestry manifests differently across climates and cultures. In temperate zones, farmers might combine nut trees with pasture (silvopasture). Tropical systems often feature fruit trees shading coffee or cacao. The key lies in selecting species combinations that complement rather than compete. Proper spacing and management ensure all components thrive.

Successful designs consider multiple time scales - quick-yielding annuals provide early returns while trees mature. This temporal stacking creates continuous production while building long-term assets. Such systems often prove especially valuable for smallholders needing both immediate food and future income sources.

Beyond Carbon: Whole Ecosystem Benefits

While carbon sequestration draws attention, agroforestry's ecological gifts run deeper. Tree canopies moderate microclimates, reducing temperature extremes and water loss. Leaf litter builds soil organic matter while roots stabilize slopes against erosion. These systems often become biodiversity hotspots, hosting pollinators, birds, and beneficial insects that enhance crop production.

The water cycle benefits particularly in arid regions. Tree roots tap deep moisture, some of which transfers to nearby crops through hydraulic lift. Canopies reduce evaporation while organic-rich soils increase infiltration. Such water-smart systems will prove increasingly vital as climate change alters precipitation patterns.

Diversified Income Streams

Agroforestry transforms single-output farms into diverse production systems. A single hectare might yield fruit, nuts, timber, fodder, and medicinal products alongside conventional crops. This product diversity provides economic resilience when market prices fluctuate for any single commodity. Value-added processing (dried fruits, artisan wood products) can further boost returns.

The long-term nature of tree crops creates intergenerational assets. While establishing orchards requires patience, mature trees often produce for decades with proper care. This contrasts with annual cropping's constant input cycle, offering farmers more stable long-term prospects.

Cultural Roots Meet Modern Needs

Many indigenous communities never abandoned integrated tree-crop systems. Their traditional knowledge, refined over generations, offers invaluable insights for modern practitioners. Blending this wisdom with scientific research creates context-appropriate solutions that respect local values while improving livelihoods.

Successful adoption requires understanding cultural perceptions of trees and land use. In some societies, certain tree species carry spiritual significance. Incorporating these cultural elements increases community buy-in and ensures the systems meet social as well as ecological needs.

Navigating Implementation Challenges

Transition complexity deters some farmers from agroforestry. Establishing trees requires different skills than annual cropping, and initial yields may decrease as systems mature. Land tenure issues can arise when investments take years to pay off. Creative solutions like alley cropping (narrow tree rows between crop strips) help bridge the transition period.

Policy barriers sometimes hinder adoption, such as agricultural subsidies that favor monocultures. Changing this requires demonstrating agroforestry's full value - not just production but ecosystem services like carbon storage and water regulation that benefit society broadly.

The Path Forward

Emerging technologies could revolutionize agroforestry implementation. Drone mapping helps design optimal tree placements, while sensor networks monitor belowground interactions. New genomic tools accelerate development of multipurpose tree varieties optimized for specific agroforestry roles. Such innovations may lower adoption barriers while boosting system performance.

Perhaps most promising is agroforestry's potential to address multiple global challenges simultaneously - climate change, biodiversity loss, rural poverty, and food security. As these pressures intensify, integrated solutions offering co-benefits will become increasingly valuable to farmers and societies alike.